Blitz by Brushstroke

A Doodlebug in St John's Wood (1944), Frank Beresford

Copyright Westminster City Archives

St Clement Danes interior looking east (1946), RG Mathews

Copyright Westminster City Archives

Damage to Peabody Buildings, Pimlico (1945), RG Mathews

Copyright Westminster City Archives

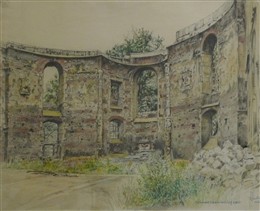

View of Bombsite in Victoria Street (1947), RG Mathews

Copyright Westminster City Archives

Damage to the roof of Westminster Hall (1941), Vivian Pitchforth

Copyright Westminster City Archives

Westminster's War Artists

By Ronan Thomas

The Blitz summons up a plethora of familiar images. These include Herbert Mason’s famous 1940 photograph of St Paul’s Cathedral shrouded in smoke and the black and white newsreel footage of grimy-faced firemen playing hoses onto burning city rooftops.

Yet these inspiring representations are only part of London’s Blitz story. No less fascinating are the perspectives left by the many official war artists who depicted the blitzed capital in prints, watercolours, oils, engravings and sketches. The prodigious talents of many leading pre-war artists are revealed in haunting and frequently surreal vistas of war-damaged 1940s London. They are strikingly reminiscent of the ruins of classical antiquity.

Wartime art

The story of London’s official war artists is inseparable from that of polymath National Gallery Director Kenneth Clark (1903-1983) and his leadership of the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC), the vital wartime arts subsidiary of the Ministry of Information (MOI). Clark, self-styled champion of art for the masses and later famous for writing and presenting the landmark BBC TV series Civilisation in 1969, founded the WAAC in November 1939, reviving a similar body set up during the First World War. Clark’s impeccable social connections - as National Gallery Director from 1933-1945, as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures at Windsor and as Head of the MOI’s Film Division from 1940 - all but guaranteed access to funding and the freedom to select artists for roving commissions.

After overseeing the temporary evacuation of much of the National Gallery’s priceless collections from London to underground tunnels in Wales, Clark set out WAAC’s vision. In wartime, art was not a luxury; it was a vital necessity, to be used to boost the morale of the nation’s civilians and soldiers. Traditional artists were as important, if not more so, as news photographers, poster makers and newspaper cartoonists. In Clark’s view:

“An artist can see new combinations of shapes and colours which most of us take for granted but which will probably convey the feel of the war for posterity, far more vividly than a photographic record can do” (1944).

As the Blitz hit London, Clark pushed this single idea relentlessly. He became the capital’s key arts gatekeeper, arbiter of arts-related ministerial and inter-service rivalry and holder of arts funding purse strings. WAAC became his driving passion. Excluding abstract artists – Clark felt that their ‘pure’ pieces held little appeal to soldiers and civilians struggling in wartime – in favour of artworks covering traditional themes of heroism, national vigour and resistance, he lobbied for inspiring pieces to be made accessible to everyone. He prioritised travelling art road shows from London to over 100 sites across Britain, including to the factories and military bases responsible for the nation’s defence.

Through his directorship of the WAAC, he played a leading role in recommending artists, agreeing salaries and purchasing their work for well-attended displays at London galleries such as at the Royal Academy in May 1941 and in galleries in New York and across the Empire.

The atmosphere of this creative period is perfectly captured by the classic short film 'Listen to Britain' (director Humphrey Jennings, Crown Film Unit, 1942). This morale-boosting piece - in which Clark appears briefly - depicts both a War Artists' exhibition and the highly popular lunchtime classical music concerts held in the National Gallery during the war.

Clark later admitted less esoteric reasons for his patronage. He wrote that his real reason for setting up WAAC “was simply to keep artists at work on any pretext, and as far as possible, stop them from getting killed” (1977). Many established and up-and-coming artists would have reason later to be grateful for such largesse, although three British war artists - Eric Ravilious, Albert Richards and Thomas Hennell - would die on active service.

Armed with easels

WAAC – endowed with a wartime budget of £5,000 –included veteran artists, academics and civil servants from several government ministries, most notably the Ministry of Information (located at London University’s Senate House in Bloomsbury) the Ministries of Supply and Home Security and staff officers from the Admiralty, War Office and Air Ministry. Clark promptly selected an inner core of (salaried) artists for commissions including Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Keith Vaughan, Anthony Gross, Edward Bawden and Edward Ardizzone. Many other working artists rushed to apply. Over 800 submitted their details to the WAAC, including several big names who had served and painted during the First World War. Amongst these were Henry Moore (subsequently famous for his 1941 Tube Shelter drawings), Muirhead Bone and Paul Nash, who produced the striking Totes Meer (1940-1941), depicting destroyed German aircraft and the air landscape Battle of Britain, August to October 1940 (1941).

A total of 400 WAAC official war artists were eventually selected and encouraged to pursue their own subjects and pitch ideas. Some were also commissioned as temporary officers, armed only with easels and painting materials. Many were allocated roles within specific ministries or attached individually to the Royal Navy, Army or Royal Air Force (RAF). By war’s end in 1945 they had produced over 6,000 artworks covering the home front, military munitions production, training and equipment, naval and air manoeuvres, transport and shipping, Air Raid Precaution (ARP) and civil defence, Blitz war damage, senior military officer portraits and depictions of ordinary soldiers in individual military campaigns.

Many well-known pre-war artists were recruited: Stanley and Gilbert Spencer, Barnett Freedman, Eric Kennington, Norman Wilkinson, Reginald Eves, RG Mathews, Vivian Pitchforth, Frank Beresford, Henry Marvell Carr, Anthony Gross, William Roberts, Eric Taylor, Richard Eurich, Adrian Allinson, Carel Weight, Rodrigo Moynihan, A. R Thomson, John Edgar Platt, William Gaunt, Leonard Rosomon, Anthony Devas, Ceri Richards, Robert Colquhoun and Mervyn Peake.

Over 40 leading women artists joined WAAC, including Dame Laura Knight (famous for her 1943 picture of munitions machinist Ruby Loftus), Dorothy Coke, Ethel Gabain, Evelyn Dunbar (painter of a popular oil and watercolour series featuring Land Girl volunteers at work in 1940), Dorethea Francis, Anna Zinkeisen, Stella Schmolle and Leila Faithfull.

The WAAC dispatched artists on short term commissions – fees ranged from £10 for single drawings to £300 for oil landscapes - to record bomb damage across Britain, particularly in the worst-hit areas such as Coventry and London. Much like journalists, WAAC artists tried to arrive at the scene of bomb incidents as soon as possible to capture the authentic, often chaotic, aftermath. In other cases – imitating 18th and 19th century artists depicting the melancholic grandeur of classical ruins - they set their easels up in the rubble, painting and sketching the weed-choked shells of London buildings months or years after they had been devastated. Several war artists – including Henry Marvell Carr, Henry Moore, Frank Dobson, Carel Weight, Edward Ardizzone, Mervyn Peake, Francis Dodd and Barnett Freedman – also had direct personal experience of the London Blitz, losing work in progress after their studios were destroyed in air raids.

Westminster's war artists

In the City of Westminster, WAAC official artists such as Canadian former newspaper sketch reporter RG Mathews, veteran royal portraitist and landscape painter Frank Beresford, art historian William Gaunt, academics Vivian Pitchforth and John Edgar Platt, animator Anthony Gross and Tube poster artist Adrian Allinson all produced wistful scenes of ruined London. These included the Houses of Parliament, hit by incendiaries on 10-11 May 1941 and opened to the elements, and the skeletal, burnt-out remains of churches such as St Anne’s, Soho, St James’s, Piccadilly and St Clement Danes, Strand.

The artists were confronted by many bleak and surreal sights on bomb sites across Westminster: the pulverised remnants of houses in St John's Wood, the shredded Burlington Arcade on Piccadilly, the Shaftesbury Theatre obliterated by a parachute mine, levelled parts of Victoria Street and alien wastelands which were once Pimlico housing estates. Sketching the remains of smashed lift shafts in West End and City buildings, artist Vivian Pitchforth described them as ‘prehistoric animals lying over jagged walls’. Paintings by these Westminster artists also included police river rescue scenes under Blackfriars Bridge and a semi-pastoral ‘Dig for Victory’ vista by Adrian Allinson showing fashionable St James’s Square SW1 transformed into vegetable allotments for the war’s duration.

After capturing scenes of the London Blitz in 1940-1941 and depicting other home front themes, a number of official war artists volunteered for overseas war service. Some, such as temporary captains Edward Ardizzone, Henry Marvell Carr and Edward Bawden, were among those sent by WAAC to cover the Middle East. Once he had painted the Blitz in Westminster, Vivian Pitchforth also served in Burma and Ceylon. The gregarious, Dulwich-born, Anthony Gross went on to paint in no fewer than three theatres of war: the Middle East, Burma and North West Europe (he waded ashore on the D-Day beaches in June 1944 holding his canvasses and sketchbooks above his head).

When the war ended in 1945, the 400 WAAC artists resumed their pre-war painting and academic careers and Kenneth Clark (Baron Clark from 1969) distributed their 6,000 pieces to the Imperial War Museum and across Britain’s network of regional art galleries and collections.

The WAAC artists’ vivid and often surprising perspectives on the Blitz were showcased in the Westminster City Archives' West End at War exhibition at the SW1 Gallery, Victoria, from 9 December 2010 to 13 January 2011.

For more on Westminster's official war artists see:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/london/hi/people_and_places/arts_and_culture/newsid_9260000/9260265.stm